Seasonal Astronomy: What I Look For in the Changing Sky

One of the things I appreciate most about astronomy is its rhythm. How the sky shifts with the seasons in a way that’s both predictable and endlessly fascinating. Each time of year offers a different vantage point into the cosmos, revealing specific constellations, deep-sky objects, and planetary alignments that aren’t visible just weeks before or after. As an observer, I’ve come to see the year as a kind of astronomical calendar, one that invites both planning and discovery.

In this guide, I’ve outlined the highlights I look forward to in each season from mid-northern latitudes. It’s not just a list of objects to observe.It’s a framework for thinking about how our position in space affects what we can see, and when. In spring, for example, we peer out of the galactic plane and into distant galaxy clusters; by summer, we’re gazing directly into the rich star fields of our own Milky Way. These shifts aren’t random. They’re tied to the geometry of Earth’s orbit and orientation.

This kind of seasonal awareness has helped me become a more intentional observer. It’s one thing to find an object in the sky; it’s another to understand why it’s there, and what its visibility tells us about our place in the universe.

If you’re just beginning your astronomical journey or looking to deepen your practice, I hope this seasonal overview helps you navigate the sky with more purpose and insight.

Spring (Mar – May): This is often called “galaxy season” because the evening sky is filled with distant galaxies (as our view out of the Milky Way faces Virgo, Coma, Leo, etc.). With a moderate telescope, try hunting the Virgo Galaxy Cluster. Even a 6″ scope can reveal the brightest members like M84, M86, and Markarian’s Chain of galaxies. In Leo, look for the Leo Triplet (M65, M66, and NGC 3628) which are three galaxies in one field of view (requires a dark sky for the faint one). Don’t miss M104, the Sombrero Galaxy in Virgo a bright galaxy with a distinctive dust lane. Spring skies also feature Regulus (the brightest star in Leo) and Spica (in Virgo) along with Arcturus climbing high. Arcturus (in Boötes) is an orange giant star. It'' is easy to spot and useful for star-hop starting points. The Big Dipper is high in spring; follow its pointer stars “down” to find the North Star (Polaris) and “arc to Arcturus, then spike to Spica” as the saying goes. Notable spring meteor shower: the Lyrids in late April (around April 22) not as prolific as Perseids/Geminids but can produce some bright meteors. In spring of certain years, you may catch Mars or Jupiter in opposition (it varies , e.g., Mars was at opposition in spring 2022, but not again until 2025). Always check which planets are visible each month; spring evenings often have at least one or two bright planets on display.

Summer (Jun – Aug): The Milky Way galaxy’s core dominates summer nights. On a moonless summer night in a dark location, the Milky Way appears as a bright cloudy river running from Sagittarius in the south up through the Summer Triangle overhead. Sagittarius and Scorpius in the southern sky are teeming with star clusters and nebulae. Use binoculars to sweep this area; you’ll stumble upon jewels like the Lagoon Nebula (M8) and Trifid Nebula (M20), the Omega Nebula (M17), Eagle Nebula (M16) all in and around Sagittarius (these glow best with a nebula filter). The Sagittarius Star Cloud (M24) is a whole dense patch of Milky Way you can observe. Just above the “Teapot” shape of Sagittarius, you’ll find Saturn hanging around most summers (Saturn reaches opposition typically in mid-late summer or early fall and is magnificent through a telescope – make sure to show friends during summer barbecues!).

The curving tail of Scorpius contains Antares (a red supergiant star) and not far from it, the M4 globular cluster. Overhead, the Summer Triangle of stars (Vega, Altair, Deneb) marks constellations Lyra, Aquila, Cygnus. Look for the Ring Nebula (M57) between Beta and Gamma Lyrae (a small smoke-ring planetary nebula). The constellation Cygnus (the Swan) is rich in star fields. The Northern Cross asterism within it is easy to spot. Under dark skies, you can see the North America Nebula (NGC 7000) near Deneb (requires a wide view and maybe a filter). Also, Albireo, the head of the swan, is a famous double star, one gold, one blue, a gorgeous sight in any telescope. Summer is also prime time for the Perseid Meteor Shower every August, around the 11th-13th, Earth passes through Comet Swift-Tuttle’s debris, yielding fast, bright meteors (with trains) radiating from Perseus. The Perseids are often the most watched meteor shower since the weather is warm; under dark skies you might see. ~60 meteors per hour at the peak. Even with some moonlight or light pollution, it’s worth looking up for Perseids in August.

Fall (Sep – Nov): As nights lengthen, the fall sky brings a mix of faint galaxies and brilliant stars of the coming winter. Early fall evenings still have the Summer Triangle lingering, but new constellations like Pegasus and Andromeda take center stage. The Great Square of Pegasus is an easy pattern to find. Just off one corner of the square, you can find the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) as mentioned, it’s visible as a faint oval smudge with the naked eye in a dark sky, and in binoculars or a scope it shows a bright core and faint extent, with companions M32 and M110 nearby . It’s the closest major galaxy to us at ~2.5 million light years away when you show someone Andromeda in your scope, remind them the photons hitting their eye traveled 2.5 million years to get there! Also in Andromeda’s constellation is Algol, the famous eclipsing binary star (it dims noticeably for a few hours every 2.87 days – a fun thing to observe over a night or two).

In Perseus, the Double Cluster (NGC 869/884) between Perseus and Cassiopeia is a must-see in fall. These are two rich star clusters appearing side by side, stunning in binoculars or a wide-field scope. Cassiopeia (the W-shaped constellation) itself is full of open clusters – M52, M103, etc. Late fall, the Pleiades rise in the east, heralding winter’s approach. You’ll also notice Capella, a bright golden star in Auriga, climbing in the northeast. Fall’s hallmark meteor shower is the Leonids in mid-November, but the Leonids are only spectacular in certain years (they have a 33-year cycle of producing storm-level rates; otherwise, typical rates are modest ~15 meteors/hour). Still, mid-November has both the Taurids (known for occasional fireballs) and Leonids, so keep an eye out. Planets: Fall 2023 had Jupiter and Saturn prominently; in general, Jupiter often reaches opposition in fall, making it big and bright for telescope viewing (its oppositions happen roughly every 13 months, moving through the calendar over the years).

Winter (Dec – Feb): The winter night sky is dominated by some of the brightest stars and most famous constellations. Orion is the centerpiece. The three-star belt and the hourglass shape are unmistakable. Hanging from the belt is the Orion Nebula (M42), which is the showpiece nebula of the sky, even visible as a faint glow to the unaided eye and magnificent in any optical instrument (it’s one of the first objects you should show friends through a telescope on a winter night). Nearby in Orion’s sword is M43 (part of the same nebula complex) and the Running Man nebula, and on Orion’s belt you also have some interesting targets (like the multiple-star system Sigma Orionis, and the Horsehead Nebula IC 434. Al though the Horsehead is very difficult visually; it’s more of an advanced object requiring a big scope and H-Beta filter).

To the west of Orion lies Taurus, with the bright red giant Aldebaran marking the bull’s eye and the Hyades star cluster (a nice V-shaped group). Higher up in Taurus are the Pleiades (M45), looking like a tiny dipper, another must-see (we’ve mentioned them a few times because they’re a delight in binoculars, revealing 6+ hot blue stars and a hint of nebulosity in photos). The winter sky has Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, gleaming in Canis Major follow Orion’s belt downward to find Sirius. Above Orion you have Gemini (with the bright stars Castor and Pollux), Auriga (with Capella and three nice star clusters M36, M37, M38), and Canis Minor (just a line with bright star Procyon). Also, Betelgeuse (Orion’s shoulder) is a red supergiant worth observing. It even underwent a famous dimming in 2019 that had people wondering if it was about to go supernova (it didn’t, and is back to normal, but as an experienced observer you can keep tabs on it!).

Winter is a great time for open clusters: besides the ones in Auriga and Taurus, check out M35 in Gemini (a rich cluster, with a tiny faint companion cluster NGC 2158 visible in larger scopes). And don’t forget Cancer’s gem: the Beehive Cluster (M44) is best seen in binoculars as a hazy patch resolved into dozens of stars. Winter’s big meteor event is the Geminids in December. The Geminids peak around Dec 13-14 each year and are often the strongest shower of the year (rivaling or surpassing the Perseids). The only downside is it’s cold! But if you bundle up, you could see 100+ meteors per hour at the Geminids’ peak under dark skies. Finally, winter often brings one or two bright planets into the evening which is frequently Jupiter or Mars. For instance, Mars was super bright in late 2022 during its opposition near Taurus (even occulating the Moon that December). In other winters, Jupiter might be shining high in Pisces or Aries. Keep an eye on planet schedules. A winter apparition of Venus in the west at dusk, or Saturn in the morning, etc., can add to the season’s highlights.

Final Thoughts

This seasonal list only scratches the surface, but it gives you a sense of how the sky’s treasures change over the year. A handy practice is to have a stargazing app or a planisphere set to each month so you can identify “what’s up” tonight and zero in on a few targets for each session. Over the course of a year, you’ll get to see the entire celestial pageant.

You May Also Like

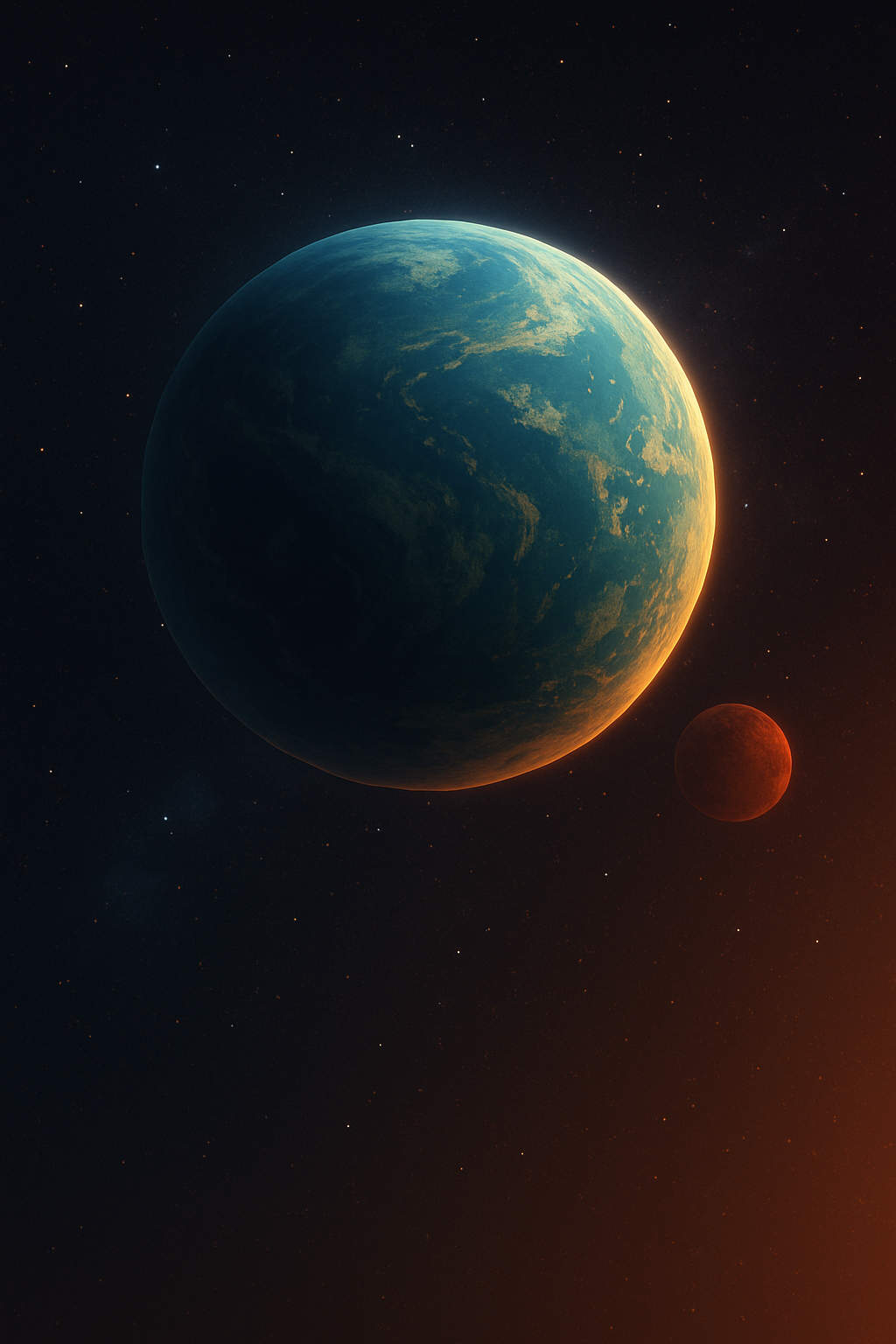

Signs of Life on Exoplanet K2-18b

Scientists have detected potential signs of life in the atmosphere of exoplanet K2-18b, sparking excitement and debate about the possibility of extraterrestrial biology.

A Beginner’s Journey Into Astrophotography: What to Know, What to Bring, and What to Expect

A practical beginner’s guide to astrophotography, covering everything from gear and techniques to capturing and editing stunning night sky images.

Top 5 Astronomy Apps to Explore the Night Sky

Discover the cosmos from your backyard with these top astronomy apps that turn your phone into a personal planetarium.

Guide to Stargazing: Gear, Apps, and What to Look For

Stargazing is a rewarding hobby that anyone can enjoy, whether you’re armed with just your eyes or a high-end telescope.

Finding Dark Sky Astronomy Sites

Struggling with light pollution? This guide walks through how to find dark sky sites, make the most of backyard observing, and reduce local light interference. Plus tips on staying safe and becoming an advocate for preserving our night skies.